Pursuing Progress

The story of Konocti Unified School District

Clearlake, California

Konocti Unified School District in northern California has a hard-working staff. The Visible Learningplus school change process, based on Professor John Hattie’s research, is helping the school system work hard in key target areas, producing identifiable pockets of progress.

A sticky problem with state learning standards is this: Departments of education set up fixed finish lines for students from the same grades to cross by the end of the school year, even though they may be beginning from very different starting points. Aside from the obvious result that certain schools and districts land at the bottom of proficiency rankings year over year, becoming the target of a variety of reform efforts, the people who work in those schools begin feeling beaten down, knowing that no matter what heroic efforts they might try, they have little chance of getting 100 percent of their kids at or above level before summer arrives.

Wouldn’t it make more sense to focus on progress over proficiency? This is the idea that no matter where children are in their individual learning, they can make a year’s gain (or more) over the course of the school year. This is a gain worth celebrating, and it helps administrators, teachers and others working in those schools recognize that they’re having a positive influence on their students.

That was the conclusion that Konocti Unified School District came to three years ago. According to Teresa Rensch, director of Curriculum and Instruction for the 10-school, 3,400-student district, and:

“We wanted to do right by the kids. We wanted to do right by the adults. We were working hard. So, we decided, let's work hard in the 'right' areas. And that means making informed decisions by monitoring what the current research says to guide us and then using evidence of our own impact to make sure we're on the right track."

Visible Learningplus in brief

As education researcher John Hattie explained in his well-known study, "Visible Learning," anything you try in the classroom is probably going to have some kind of positive impact on student learning. If that’s the case, why not work on those factors with the strongest outcomes? Currently, Hattie’s research examines and synthesizes more than 1,600 meta-research projects covering over 95,000 studies to rank over 256 effects that influence learning outcomes. Those effect sizes greater than 0.4 accelerate student learning.

In the Visible Learningplus school change model of professional learning, teachers gain clarity about the impact they have on student learning through ongoing cycles of evaluation, and every student gains knowledge and skills that enable them to become teachers of their own.

Seeking New Solutions for a Challenged Region

The challenges for Konocti (pronounced "co-knocked-eye") are many. This region of Northern California has been hit by devastating wildfires, delaying the school start four years running. A large number of families are hobbled by unemployment, addictions and poverty, and a sizable share of students deal with homelessness. Nearly a quarter of students are English language learners (and in some of the schools, the share is closer to a third of students).

On the staff side, teacher transience has been an issue. About a third of teachers aren’t fully credentialed. They have bachelor’s degrees and have passed the required tests, but they haven’t necessarily been trained as teachers.

Rensch arrived after a career as a middle school principal at another California district with a background in Visible Learningplus. She’d been introduced to the work of John Hattie when a teacher at her school gave her a copy of one of Hattie’s early books. "Reading the book changed me," she says.

"We have lots of lists of what we’re supposed to do in education but we don’t always know how well it’s working or who it’s working for."

The Visible Learningplus approach had helped Rensch gain focus in her activities at the previous district, to make sure she and her teachers were "hanging onto what we needed and how we delegated and prioritized." She brought that focus to Konocti, where the top administrators and the school board were open to learning more about Visible Learningplus. In summer 2016, a year after Rensch joined the district, she took a group of site administrators, instructional coaches and members of the executive cabinet to a Visible Learning conference, where Hattie himself gave the keynote.

That introduction helped shore up the idea, recalls Rensch, that "we should be able to guarantee every kid one year’s growth or more." Right then and there, during the conference, Konocti leadership knew Hattie's research was worth rallying around. "People liked the idea of finding assessments to track our progress along the way. They liked the focus on literacy. They liked the idea of narrowing the focus to just a few fundamental strategies that we were already implementing or could implement even better across the board."

Focusing on the four pillars

By the time they’d returned, the group had mapped out a strategic plan that called for every educator in the district to receive professional learning on Visible Learning’s basics through "foundation days." The teachers learned about Hattie’s research and why it’s considered so convincing, as well as four key ideas of Visible Learningplus that resonated with Konocti leadership as areas of focus, which they coined the "four pillars”:

None of these concepts were new to the teachers, Rensch insists. But the idea was to "be really clear on what the essential learning is, what you want the students to know and be able to do and make that visible and bring it to life for the kids."

For example, the teachers learned that when the relationships they have with students are positive, students feel safer and they become less fearful of taking risks. Students also begin understanding that making mistakes is all part of the learning process. They’re also more likely to feel positive about school and begin to develop a love of learning.

In the area of clarity, rather than setting up an agenda for the day, teachers would begin talking to their students about the learning that was going to happen during the day and what success would look like. The student perspective shifted from, "I’m going to do these 10 problems" or "I’m going to drop this paper off in the outbox" to "I’m solving a two-step equation."

Feedback Without Clarity is

Meaningless...At Best

That change is "huge," says Rensch. "Simple yet super-profound because the student is involved in understanding what is essential about their learning and what success looks like. They can articulate it and be empowered to take next steps with that."

Once students know what it is they’re learning and what success looks like, Rensch adds, they can start to have command over "their game plans, to assess where they’re at and take next steps to advance their learning or solve their own problems—what we want for them in life."

Previously, Rensch explains, assessment was "what went into the gradebook at the end of the week." Now, it has become "all the different ways staff and kids are checking for understanding—frequently, every hour—whether that’s picking raised hands, using popsicle sticks, doing think-pair-share, tapping exit slips, white boarding or something else.”

Feedback, an area that Rensch acknowledges is something the district is still working on, involves making the assessment outcomes visible and helpful enough to deepen the learning and give students a map for the next steps in their learning. And it isn’t only coming from the teachers, she adds. When students themselves are clear about learning intentions and success criteria, they’re better positioned to be able to give useful peer feedback and even self-feedback.

The pillars are fundamental to seeing progress and knowing the impact, she emphasizes. "They’re embedded in any content area, any pedagogy, any grade level, any age—including adults. We want good, strong relationships with our bosses. And we like to have clear expectations on what success looks like for us to do our jobs well. We want feedback that helps us understand what's next."

How a teacher uses Visible Learningplus to level the playing field

Konocti Education Center is an amalgam of several programs in one location, including a school for the arts (for grades 4-8), a middle college pathway and a magnet school for health sciences (for grades 7-12).

Robynn Giese teaches all of the science courses for the high school, a total of 12 different classes, reaching every high schooler, many of them in the room at the same time. She believes the Visible Learningplus strategies she’s picked up have enabled her to differentiate the learning for her students.

The taxonomy Giese uses is based on a model of learning which has three levels of learning:

- Surface: where the student knows a handful of ideas but can’t necessarily relate them;

- Deep: where the student can connect the ideas but not necessarily apply them; and

- Transfer: where the concepts can be applied to different scenarios.

She likes the use of this "leveled success criteria," because it helps students learn how to learn. Typically, the surface knowledge for the science students begin with vocabulary, and especially being able to explain terms in their own words. When the students believe they’ve reached a surface level of understanding, either through vocabulary activities or watching short videos and producing Cornell notes, they’re expected to do a "learning check": They create a video on their Chromebooks in which they explain the vocabulary based on their success criteria.

Once Giese has approved the student videos, they’re allowed to move onto the "deep learning." Here they’re engaging with the content more, and frequently that involves lab work. And once they’ve provided evidence to support that, they’re allowed to move onto project work. For instance, in a lesson about evolution, whereas the "regular" biology students will learn about the topic in general and develop a more traditional project, the medical students will tackle a project on bacteria and how they evolve to become antibiotic resistant.

But the point is that the leveled success criteria provides a mechanism for giving each group of students "small steps so that they are never too overwhelmed; and they’re given a lot of choice in terms of assignments so that they can be successful at that level."

Making the learning visible has myriad advantages, Giese says. A biggie is that the process itself puts everybody on a level playing field. "We all start off at surface and really have to work and learn and follow the success criteria to get up to transfer."

As a result, the process slows down students who just want to be done and "who like to speed through things just because they want that reward—an A from the teacher" and stops them from doing "treasure hunting," attacking the reading in search of specific answers. And it sets up "baby steps" toward progress for the students who might have issues such as chronic absenteeism going on in their lives. In that case, she adds, she can spend more time with those students that "might perhaps need more assistance from me directly."

"We all can have the same learning intention and be doing some activities that are similar," Giese explains. "But then also, depending on which class you’re in, you can have a different set of success criteria for that learning intention."

A principal's hunt for impact

Shellie Perry moved to Konocti three years ago from another, more affluent district with the intention of growing in her profession. And that’s exactly what happened. She began as a teacher at the same time that Visible Learningplus was being introduced into the district, became an assistant principal and then principal. Now she leads Burns Valley Elementary School, a preK-7 with 537 students. While Perry recognizes up close the challenges the district has, she also emphasizes the "amazing set of students and teachers" at her school—"so we’re pretty lucky actually."

Her exposure to the concepts of Visible Learningplus began with the vocabulary, putting "new names to things." "Learning objectives and outcomes" became "learning intentions and success criteria," and those were shared with the students. "Teacher-student relationships" became "positive and inspired teaching and learning," which has influenced the new hires she makes for her school. As she explains, "I really want to get people who are positive and ready to jump on board and continue the journey that we’re on."

The district began doing walkthroughs in classrooms, consistently looking for evidence of the four pillars and asking kids three questions:

- What are you learning?

- How will you know when you’ve learned it?

- Where to next?

At Burns Valley, the walkthrough notes based on observation notes follow a checklist and turn into immediate feedback that’s left for the teacher. Then, once a week, while the students are in PE, the grade-level teachers meet on site, and that quantitative evidence gathered from the walkthroughs, along with writing samples, outcomes from state testing and other data points, are used to target professional learning.

Perry offers an example. The California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress (CAASPP) scores from last year showed that English learners (32 percent of the student population) were the school’s primary underperforming group. This year, in response, teachers put the focus on that group of students, going through professional development that was all around English language learning and developing a rubric and new assessments specifically for English learners, which will see full implementation beginning in the new school year.

9 Ways for Students to Own

the Assessment

"From there my team of teachers here looked at all the strategies and determined which ones were going to be the highest impact, and they all agreed that they were going to use those in their classrooms," Perry says. "That’s what I’m looking for when I’m walking through classrooms: Are they using the strategies? Do they need my support? How can I make this more effective for them? How can I help them through this process?"

As one example, grades 2 through 7 are doing a lot of work with close reading and rereading of passages for different reasons and different outcomes. The activities include explanations to the students about "what they’re looking for when they read this passage multiple times, why they’re looking for that and why it’s important for them." The big lesson for them, she notes, is that "using the same passage allows you to dig deeper within each layer that you peel back. It’s a strategy that’s proven to [have impact] for all students, and we’re using it even further to target [English language development] students."

Monthly or every six weeks, the teachers do pretests and post-tests as formative assessments—"little checks built into our school year," as Perry puts it. But currently, the school is awaiting the current year’s CAASPP scores—"what the state is reviewing us on"—to see how those efforts have moved the needle. Once they have those in hand, Perry says, they’ll adjust and continue moving forward.

But Perry already expects good news. "Our first-grade is one of our powerhouse teams. They are making that one year’s growth in one year’s timeframe, and sometimes more than that," she says. "Most of my grade levels are showing almost one year’s growth based on the effect size that Professor Hattie had developed. So overall we are definitely making progress."

Showing consistent district commitment

Ainsley Rose, a long-time Corwin education consultant who has worked with Konocti educators and administrators on several occasions, calls out one attribute in particular to be applauded in the district. That’s the evident commitment on the part of district leadership to develop what MIT’s Peter Senge has termed the "learning organization."

Even the director of human resources or the director of finance will sit in on Visible Learningplus sessions and fully participate, says Rose. The same is true for principals and instructional coaches. "The fact that they are consistent and they’re staying the course is an element of success that will eventually lead to greater success because they continue to focus on professional learning."

Too often, Rose points out, principals or district leaders will greet him and his Corwin colleagues on arrival, personally introduce them to the faculty and then "leave the room." When that happens, he notes, it’s a signal to the teachers that the principal isn’t necessarily a learner. "If we want learning organizations, everybody in the organization must be learning and that has to be modeled from the top down and from the bottom up. Kids need to understand that teachers learn along with students. And teachers need to understand that principals learn along with teachers, and so on all the way up the food chain."

"From there my team of teachers here looked at all the strategies and determined which ones were going to be the highest impact, and they all agreed that they were going to use those in their classrooms," Perry says. "That’s what I’m looking for when I’m walking through classrooms: Are they using the strategies? Do they need my support? How can I make this more effective for them? How can I help them through this process?"

As one example, grades 2 through 7 are doing a lot of work with close reading and rereading of passages for different reasons and different outcomes. The activities include explanations to the students about "what they’re looking for when they read this passage multiple times, why they’re looking for that and why it’s important for them." The big lesson for them, she notes, is that "using the same passage allows you to dig deeper within each layer that you peel back. It’s a strategy that’s proven to [have impact] for all students, and we’re using it even further to target [English language development] students."

Monthly or every six weeks, the teachers do pretests and post-tests as formative assessments—"little checks built into our school year," as Perry puts it. But currently, the school is awaiting the current year’s CAASPP scores—"what the state is reviewing us on"—to see how those efforts have moved the needle. Once they have those in hand, Perry says, they’ll adjust and continue moving forward.

Seeing daily evidence of progress

The influence of Visible Learningplus hasn’t reached all corners of the whole school system yet. It’s still—and will always be—a work in progress. That’s the nature of learning. As Rensch notes, "We all have room for growth."

As Perry, the newest principal in the district explains, "We aren’t all in the same place but we’re all doing a lot of the same things. As principals we meet twice a month, we bring our data to our meetings about what we saw when we walked through classrooms, and we agree on our standards as principals and what we are going to do: We are going to be visible in classrooms; we’re going to provide feedback; we’re going to model what we’re asking our teachers to do."

But it’s the students themselves that daily convince Rensch the district is on the right track.

"To walk in and have the kids drag me over because they want to show me what they’re reading or what their reading goal is or that they’ve met their reading goal, and they can talk about the steps they took to reach that goal. Not what the teacher did. Not what the assignment was. That’s been really exciting."

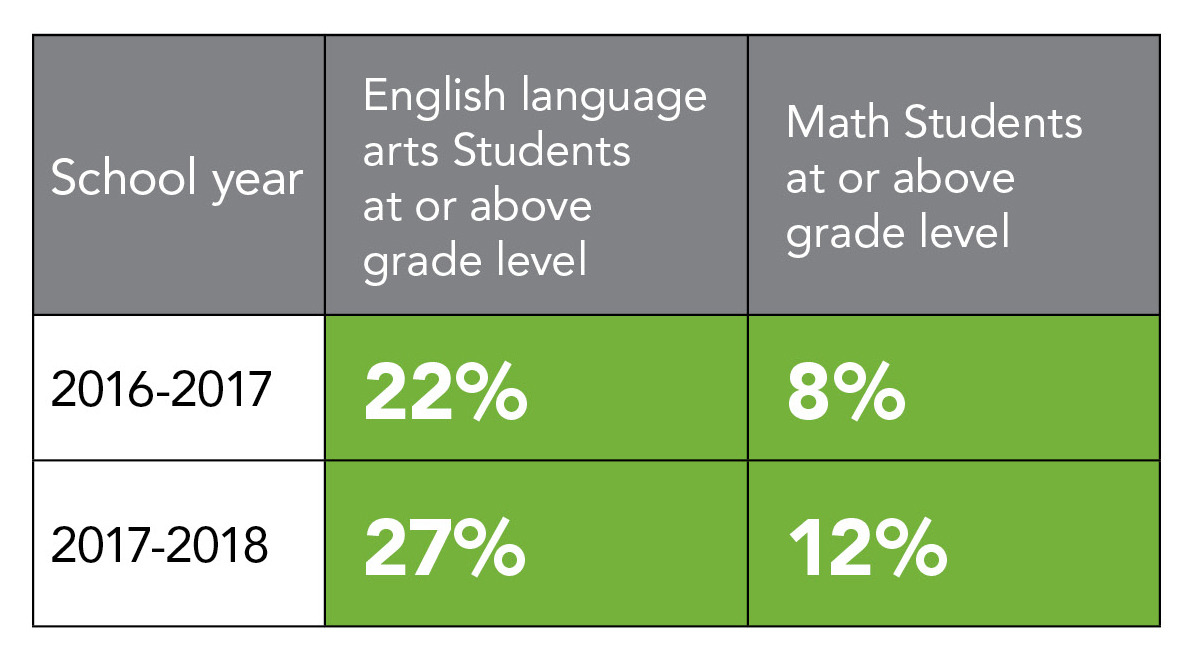

Evidence by the numbers

While the total percentage of students deemed proficient at Konocti Unified is low, the share of students gaining a year's growth for a year of school—making progress—is on the upswing since the advent of Visible Learningplus.

1Hattie, John and Gregory Donoghue, "Learning strategies: a synthesis and conceptual model," npj Science of Learning, 2016, https://www.nature.com/articles/npjscilearn201613.

p;

p;

Download and share!

"We wanted to do right by the kids. We wanted to do right by the adults. We were working hard. So, we decided, let’s work hard in the ‘right’ areas."

Dive Deeper